- Home

- Kathryn Gossow

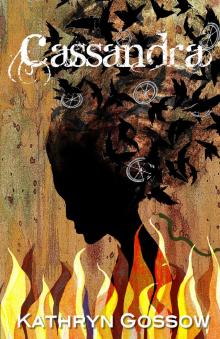

Cassandra Page 5

Cassandra Read online

Page 5

‘What?’

‘You know very well what. Keep your feet still.’

Cassie turns towards the picture. If she lets herself go cross-eyed, the new princess’s face goes blood red.

The Royal Wedding happened a year ago. They all watched the wedding on TV, except her mother. ‘What’s some blonde bimbo got to do with Australia,’ she’d said and Ida called her a republican and so she’d gone to bed. Her dad didn’t say anything, but Ida and Cassie thought her dress was beautiful. Imagine being born and living a life and then one day—bam—suddenly a prince looks at you and you become a princess. How could you see that coming? Could anyone think that would happen to them?

Still, it is weird what the magazine cover is doing. Like a hologram. Normal, skeleton, blood.

The dental nurse opens the surgery door. ‘Alex Shultz.’ She smiles with perfect teeth.

‘Alexander,’ her mother corrects as she stands and tucks her bag under her arm.

Alex sits unmoving, his teeth clenched.

Cassie elbows his arm. ‘Go on, Alex, the dentist’s got his drill ready for you—dddrrr.’

‘Cassie!’ her mother says.

Alex stands and trips on the edge of the rug.

‘Careful, Alexander,’ her mother says gently.

‘Yes, careful, Alexander,’ Cassie echoes less than gently.

Her mother follows Alex through the door, turning back to mouth, ‘Behave,’ in Cassie’s direction.

Cross-eyed—the princess’s face blood red. Corner of her eye—princess’s skeleton. Cross-eyed, blood. Corner of eye, skeleton. Cassie leans closer, turns her head; still a skeleton. She reaches for the magazine and picks it up. The magic disappears. The princess’s amazing blue eyes sparkle back at her. Cassie throws the magazine back towards the coffee table and it slides to the floor. The lady at the desk looks up and pulls her glasses down her nose, her not-sparkling blue eyes telling Cassie to pick it up. Cassie kneels down with a humph noise and there it appears—under the coffee table another magazine, lost for her to find: ‘10 Hearty Winter Recipes’, ‘Gorgeous Jumper Patterns for Him and Her’, and ‘Reveal the Future—The Secret of Palmistry’.

Cassie runs her finger down the contents page and finds the article on page eight. She skims through the four pages of diagrams. The heart line. The head line. She glances at her own hand. Sometimes she could say when unexpected visitors were coming; she just knew. She dreamt how many kittens Casper would have, and she was right. She knew the day her mum lost her purse something bad was going to happen. She just didn’t know what. Then there was the whole thing with Natalie and her broken arm. But those were stupid things. Little things. Not big things like droughts or when to plant the wheat, or who would be a princess and who wouldn’t.

Cassie locates the life line on her hand. She wants it to be long, but it stops abruptly long before the base of her palm. She traces the line with her finger. It is crisscrossed with faint lines. Crisis and worries in your life, the magazine says. The head line, boring. Just a line. The heart line, a mess of broken lines. Death and loss of relationships. Depressing.

Her short fingers say she acts on impulse. That doesn’t tell her about the future.

She closes the magazine, slams it onto her lap, and flings her head back with a loud sigh. The walls of the waiting room have been painted since they were here last year. They used to be smooth and white; now they are pale pink and textured, as if they painted them with a wet paint brush. There are new pictures too. All blue in some way. A flock of seagulls soaring over an ocean, a vase of blue flowers—are they what the flowers books mean when they say cornflowers? English books are full of cornflowers but she’s never seen a real one.

And a picture of a little boy dressed in blue holding an apple. He looks a bit like Alex did when he was a baby. The boy has chubby smooth hands. Alex’s hands used to be so little. She could put his whole hand in her mouth and make him giggle. Smooth, lineless hands. Ida and Poppy have millions of lines on their hands.

She sits up and looks at her palms. The lines on hands must change. What does that mean about the future? Is it like hard toffee or a gooey wad of gum?

‘Cassandra Shultz.’ The nurse stands in the doorway.

Alex slumps in the seat beside her. ‘I got to come back for a filling.’

‘Come on Cassie,’ her mother urges from behind the nurse. Cassie leaps up, feeling tall on her legs. She smiles at the nurse and the dentist. He smiles back and she climbs into the chair.

‘Dr Maywood, can I keep this magazine?’ She holds it up for him to see.

‘Cassie, don’t be rude.’ Her mother sits in the mother’s chair against the wall.

Dr Maywood lowers the examination chair and turns on the light above. ‘With those beautiful teeth, how could I say no? Give it to your mother to mind and open your mouth for me, possum.’

Her mother looks at the magazine. ‘It’s a year old, Cassie. What on earth do you want it for?’

‘Knitting pattern,’ she manages to say as Dr Maywood stretches her mouth open to inspect her teeth.

‘What did she say?’ her mother asks.

‘I think she said “knitting pattern”,’ the nurse replies.

‘She can’t even knit,’ her mother says, shoving the magazine into her bag.

* * *

Cassie steps onto the front veranda, reciting the lines in her head. She doesn’t want to use the magazine. It doesn’t seem … professional.

On the veranda sits Aunty Ida, sweating in her church stockings, Poppy wearing his usual blue singlet, and Alex bent over his weather notebook. Each has a teacup, even Alex. Cassie puts her glass of green cordial on the table. Poppy’s radio crackles in the background. The sky, pale and devoid of clouds, opens like a hand above them.

‘Aunty Ida, can I read your palm?’

‘Where would you get such rubbish, girl?’ Ida says.

‘I’m good at it, promise.’

Ida holds out her hand and turns to Poppy. ‘I hear someone moved into the old Schmidt place.’

Cassie strokes Ida’s palm, the skin soft and spongy, the tips of her fingers calloused and stained the colour of the garden’s red dirt. The millions of lines on her palm like a piece of paper that’s been screwed up and flattened out.

‘Needs some work, that old place. Can’t think who’d live up there,’ Poppy replies.

Cassie draws her finger through the crevice of Ida’s long, deep life line. Near the beginning, a deep line cuts through it. Maybe that was the war. And Aunty Ida losing Uncle George. At the end, the life line becomes shallower, wavy and crisscrossed. ‘You’re going to live a long life, Aunty.’

Ida laughs. ‘I’ve already done that.’ She turns to Poppy. ‘Some fellow from town bought it. Theresa from the shop said he’d come in there. He said he was some sort of artist, wanted a retreat for his work.’

‘A what!’

The heart line broke in two, the second part deep and curved. An emotional loss and a caring nature. Cassie already knew that. What did Ida’s hand look like when she was young? Was the broken line there then? There was no way to tell. How could you follow a hand through its life? She doesn’t have time for that.

‘Sculptures. He makes sculptures. Apparently they pay big money for them.’ Ida laughs. ‘Theresa said he had a beard like some old swaggie—you could get lost in it, she said. Go in and never come out.’

‘I saw them,’ Alex pipes up.

‘When?’ Poppy asks.

‘I was in the top paddock. Dad sent me up to check the fox traps. You can see the house from there.’ He bends back down to his notebook.

Cassie turns Ida’s palm and looks at the marriage line under her finger. But it has a child coming out of it—that isn’t right.

‘Aunty, did you ever have a child?’

Ida snatches he

r hand back and picks up her cup of tea and turns to Alex. ‘What do you mean “them”? His wife?’

‘I don’t know. I saw them come up their drive. They had one of them Kombi vans. I don’t think it was his wife. She looked younger. Cassie’s age maybe.’

‘Hey, a friend for you, Cassie.’ Poppy winks at her.

‘Maybe. Can I read your palm?’ Cassie moves to sit cross-legged at Poppy’s feet. He holds out his palm and Cassie smooths it with her fingers.

Ida’s chair scrapes over the floor. Her sturdy high heels thunk across the veranda as she returns to the house, leaving behind her half-drunk cup of tea.

‘Cassie, darling, don’t ask your aunty about children again,’ Poppy says.

‘Why?’ She looks up at his face. Could the lines on a face be read too?

‘Just don’t.’ The creases in his forehead deepen like the gullies they dump old car bodies and tree trunks in to try to stop soil erosion. He takes his hand back and reaches over for Alex’s weather log. ‘Give me a look at what you got, boy. Anything interesting on the horizon?’

Cassie stomps down the veranda stairs onto the dry grass. It crackles like fire under her bare feet. Some rain on the horizon would be nice. But not even Alex could make it rain.

It’s raining. Poppy says she should come to his room. To see the rain. When she gets there his bed is gone and the room is big, bigger than their whole house. It’s like a science lab with instruments and a line of telescopes looking out a huge window. Really, Poppy says, I just wanted you to meet somebody. See over there. He points to a girl by the window. But the girl doesn’t interest Cassie. There’s a knocking coming from the cupboard. Who’s in the cupboard? she asks. Never mind that, it is just Ida’s baby. Poppy and the girl look through the telescopes together. No wonder Ida is unhappy; her baby is stuck in the cupboard. She opens the cupboard but instead of a baby there’s a grown boy. He has scratches on his face that dribble blood like red ink over his cheeks. Cassie thinks it looks like words. She could read them if she gets close enough. Poppy pulls her away. Never mind about that, Poppy says. That’s ancient history.

~ 10 ~

Life Saving

Cassie waves her arms, herding the mob of cattle forward. On either side of her, Poppy and her father slap the rear ends of any stragglers on the edge of the herd.

Her father glances back. ‘Alex, get up to it. Stop daydreaming.’

Alex runs up from behind and steps into the line. ‘Giddy up,’ he yells at the cattle.

‘They’re not horses, you idiot,’ Cassie says.

‘I don’t care.’

Their father looks over at them and Alex waves his arms. ‘Come on, move up.’

The ruts in the ground tell the story of the herd passing through in muddier days, but today the cattle kick up powdery pale dust from between the tussocky grass. With only two bulls and the best of the breeders, the herd has been cheaper to feed through the dry. Bales of lucerne are getting harder to come by and more expensive every month. This season’s calves have to pay their way, the whole herd’s way, and make some on the side.

‘Thank god for the chooks,’ her poppy says almost every other day. What he means is, Alex is God and the whole family should worship him for predicting a drought out of the middle of nowhere. The Shultz Empire survives in the face of drought, while their neighbours go deeper into debt, hoping for some rain to raise their crops.

‘Alex, you’re so useless,’ Cassie sneers at him.

‘What? I’m keeping up.’

‘Stop daydreaming.’

‘Leave him alone, Cass,’ her father snaps. ‘We’ll be at the yards soon.’

The green and grey cow pats mark the paddocks as the domain of the cattle; the cattle yards mark the existence of the humans who farm them. The fenced in acre, with towering windmill; Poppy’s first old Ford, riddled with bullet holes from his target practice days; and in the centre, like a rustic sculpture, the cattle yards.

At the yard, the family position themselves to round the splayed herd into the yard gate. The escape routes covered, they wave their arms at the milling line.

Alex swings off the edge of the gate, clinging with one arm, and waving at wayward cattle.

As the last cows approach, Alex leaps off the gate and runs behind it like a bulldozer. Two young steers make to escape along the outside of the rail. Cassie closes in and they turn back through the gate.

‘Almost lost ’em.’ Her father slaps his hand on a fence post, grinning.

‘Told you he was useless,’ Cassie says.

‘Shut up—it wasn’t my fault.’ Alex charges at her, ramming his head into her chest.

‘Ow!’ Cassie shoves her hands against Alex’s shoulders. He falls back, slamming his head into the yard rail. No blood spurts, just tears.

‘Cassie, leave your brother alone.’ Her father steps towards them.

‘He started it.’

‘You’re old enough to know better. Alex, go and help your mother with the fire.’

‘He bruised my chest. If I get cancer it’ll be his fault.’

‘You gotta have something to get cancer on,’ Alex mutters as he walks past her.

Cassie gives him the forks.

‘I saw that.’ Poppy shakes his finger at her. ‘Just settle down, girlie.’

Cassie grunts and climbs the yard railings and sits on the top rail. She runs her hand along the grey wood, smooth with age and wear. ‘Sorry tree,’ she whispers as she always does.

Poppy chopped this tree down, maybe decades ago, split it into rails, and dovetailed the rails into the posts. Men from other farms helped. They did that in those days. Poppy said they had a big party when they finished. The house heaved with people, he said. How come we don’t have parties now? she wanted to know. He’d shrugged, looked at her mother and lifted his cup to his lips.

Across the other side of the yards, Alex and their mother turn the coals on the fire. They went to a cent sale once. Cassie was excited she’d won a hand washer with crocheted edges. ‘Can we come next time?’ she’d asked. ‘Uneducated cow cockies’ wives,’ her mother had said in reply. They never went back to the cent sales, even though Aunty Ida helped to organise them and always made prizes for them. Cassie didn’t understand until now. Her mother was a snob. That was why there were no parties at their house.

The men in the yard separate the calves from the cows. The cattle shuffle restlessly, rubbing against each other and moaning in low drones, twitching their tails with annoyance. A lone crow calls from the empty dry sky.

Cassie slides down the rail, lowering herself into the cattle yard. Her legs dangle inches from the ramming, rattling, near-panicked beasts. Her arms hook around the rail, the strength of her shoulders holding her aloft from the dust-flinging hooves. The tang of cow poo stings her nostrils.

‘Cassie!’ her mother’s voice rapier, ‘get out of there before you get hurt. Come here and help.’ Cassie hooks her heels on the bottom rail and pushes herself back up to the top. She swings her legs over to the human side of the divide and jumps to the ground, a satisfying jolt up her legs.

By the fire, Alex idly turns the brand around in the coals. Poppy climbs over the yard rail, wiping the sweat from his face. ‘They’re sorted. Some lunch and then we’ll get started. Alex, leave it still, it won’t heat up with you turning it.’

Cassie plucks a stem of grass and chews on its end.

Her mother smacks a bug crawling up her leg and looks up at Cassie. ‘Get that thing out of your mouth, there’s no need to copy your father’s bad habits. Go and tell him to come get his lunch.’

Cassie throws the grass on the ground and walks around the side of the yards past the ramp where on Monday the cattle truck will back up and load the fattened stock off to their bloody deaths. She plucks another piece of grass and puts it in her mouth, tasting the moisture squeeze

from between the fibres. She finds her father preparing the rope where he’ll bleed a beast’s carcass at the end of the day. ‘We’re having lunch.’

Her father loops the rope around the peg and pulls the knot tight. Where the rope dangles, deadly like a noose, he grasps and lifts his feet from the ground, testing the weight.

‘Lunch,’ Cassie says again and walks back to the fireside.

Her mother’s eyes are like craggy cliffs. She swats the flies from her face and grits her teeth at them. Poppy drops himself on the log by the fire with a sigh as big as a tired old bull. Cassie rests her hand on his sweaty shoulder and he wraps his arm around her waist.

‘You should look after your brother,’ he says to her. She nods. She wants to but something about him fires her up when she sees him. ‘I’ll try, Poppy.’

She brushes her hand over the skin on his bare shoulders, gritty with dust, picks off the grains of dirt, stuck fast with sweat and hard work; the fire like music, crackles, snaps and sizzles with exploding sticks; the sun a prickly blanket circling her shoulders, scratching her face; and there is a grain of dirt that won’t come off and she scrapes the grain of dirt harder, digs at it with her fingernail, a bead of blood appears, and it smells putrid: a rotting carcass, a calf stuck in the mud and perished by heat exhaustion and thrust and broiled in the sun and maggot-filled by blow flies. Then it is her poppy, maggoty and dead, dark in box, heavy with dirt above him, and her weeping in her bed.

‘Cassie, you’ve gone off with the fairies,’ Poppy says, and the grain of dirt is not a grain of dirt, but a bleeding spot of brown skin.

The present re-forms around Cassie. The dust, the flies, the cattle yard. Something must be said. ‘The spot on your back smells bad. Badder than a dead cow.’

‘There is no such word as ‘badder’,’ her mother says, holding a container of sandwiches in front of them. Thick white bread, slabs of ham and golden pickle. All Cassie can smell is the dead cow beading in a drop of blood on her grandfather’s back.

‘See, Mum, it’s bleeding.’

Cassandra

Cassandra