- Home

- Kathryn Gossow

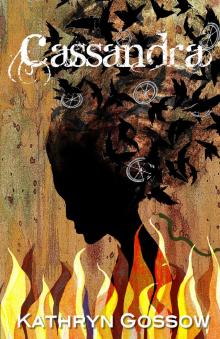

Cassandra Page 9

Cassandra Read online

Page 9

Her mother’s hand on Cassie’s back steers her towards the car. ‘It had better work out like you planned.’

‘What’s happening?’ Cassie asks, skipping ahead of her mother.

‘Oh course it will work out. Two sheds full of Alex’s chickens and we’ll do twice as well. We’ll be rolling in it,’ her father says, unlocking the car door.

They were always Alex’s chickens, even though Alex never went near them. Too rowdy, he always said with his hands over his ears.

‘The proof will be in the pudding.’ Her mother opens the car door. ‘Get in, Cassie.’

But Cassie stands on the footpath, her light feeling flipping like egg on a hot grill. She is having a Sense of Foreboding. She described the brick in her stomach feeling to Athena once. ‘A Sense of Foreboding,’ Athena had said, nodding her head. ‘Write those down.’

To the section in her notebook titled Sense of Foreboding she would add ‘Mum and Dad went to the bank. The proof will be in the pudding.’ She would not write about Paulo, or Natalie.

~ 16 ~

Reading

Tiny ants swarm over Cassie’s hand. She flicks them off. Athena’s house has no clocks. Not because, Athena claims, there is anything wrong with clocks—some people need them. Cassie for instance needs some precise measure of time to ensure she catches the school bus at 7.35am, or thereabouts, each morning. Athena and her father, needing to be nowhere at any particular time, could allow the day to lead them, rather than any measure of where the big hands are on a clock face. That is all well and good for Athena, but less pleasing for Cassie with ants crawling on her fingers, the damp ground wetting the bum of her shorts and the humidity squeezing sweat from her brow, her armpits, behind her knees, even the soles of her feet. The imprecise measure of ‘Sunday after lunch’ meant Cassie waited under the pepperina tree behind the old grey shearing shed every ‘Sunday after lunch’ for in the best instance ten or twenty minutes. At the worst, she had waited three hours.

And yet, as Athena appears over the embankment each week, a smile lights up Cassie’s face.

‘How long this week?’ Athena asks as she sits beside Cassie and folds her tanned legs beneath her.

Cassie consults her watch. ‘One hour and twenty minutes.’

‘Have you noticed that you wait less as the days get longer?’

‘No, it is all over the place.’

‘Mmm, maybe I should write it down, see if there is a correlation.’

‘Maybe I should buy you a watch.’

Athena laughs and nudges Cassie with her shoulder. ‘At least I know where I am at any one time. Where have you been this week? Spend any time in the year 2000?’

‘God, I can’t believe we will still be alive then. Do you think they’ll call it two thousand or twenty hundred?’ She counts on her fingers. ‘We’ll be thirty-two years old! Ancient.’

‘How’s school?’ Athena asks.

‘School sucks.’

‘What are you doing in science?’

‘I don’t know—something about chemical reactions. I don’t get it.’ Cassie shrugs.

‘Father and I are dissecting frogs.’ Athena’s eyes widen.

‘What?’

‘Anatomy, nervous system, heart, kidneys. I’ve been drawing them. Do you want to see?’ Athena reaches into her bag.

‘No.’ Cassie shakes her head.

‘All right, but if you dissect a frog in science you can borrow my notes. I’m getting a bit bored with frogs though. Do you think you could get me a chicken?’

‘No.’

‘What about history?’ Athena asks.

‘World War II, causes and effects.’

‘Done that.’

‘Maths?’

‘I don’t know, some chance thing, like if you throw two dice what are the chances of throwing a double six.’

‘Probability. I love probability. Have you got any worksheets?’ Athena holds out her hands.

‘No, it’s all in the textbook.’

‘Did you bring it?’

Cassie pulls the textbook from her bag.

‘Cool.’ Athena opens it. ‘There are one hundred and twelve red marbles and three hundred and two blue marbles. Each time a marble is drawn from the bag, it is returned before the next draw. What is the probability of drawing a red marble? That’s too easy.’

‘Do you have to do it now? Do it later. Bring the book to my house tomorrow, after school. I don’t have maths on Mondays.’

‘I can’t come to your house. Someone will see me. I’m a secret, remember.’

‘You’re not a secret. I already told you, everyone in my house knows that you live up here.’

‘Yes, well you were supposed to keep my secret.’

‘You should come and meet Aunty Ida and Poppy, they wouldn’t tell anyone about you. They don’t even know anyone who works for the government. We’ll tell them you go to a private school in town. They won’t even know the difference.’

‘Maybe, one day. I’ll think about it.’

‘You could sneak into my room again.’

‘I don’t need to. We have a meeting place now.’

‘Why can’t I come to your place then? Your father won’t even know I’m there. I won’t touch anything to do with his sculpture. I won’t look at it or anything.’

‘He will. He always finds out everything eventually. Come on, where’s your sense of adventure?’

‘I have a sense of adventure. I just don’t think sitting under a tree doing maths on a Sunday is all that adventurous.’

‘And doing it at my house would be?’

Cassie sighs. ‘A least it would be comfortable.’

‘Hey, maybe when we’re done, we can work out the probability of the success of each of your visions.’

‘What if some of them don’t happen until twenty hundred or two thousand or whatever it will be called.’

‘I know, it is annoying, isn’t it? This is way harder than dissecting frogs. I almost forgot, speaking of a sense of adventure.’ She riffles around in the bottom of her bag and pulls out a small jar. ‘Ta dah!’

‘Something new?’

Athena nods, passing the jar to Cassie.

Cassie looks through the glass, ‘Grapes?’

‘No silly, olives.’

Cassie unscrews the lid. ‘Are they sweet?’

‘No no, don’t expect it to taste like sweet. More bitter.’

‘Okay.’ Cassie picks out the glossy, slippery fruit with her fingers and holds it up.

‘It has a seed too, it’s call a pit or a stone,’ Athena says. ‘They don’t always have seeds, sometimes they take them out, but these ones have seeds.’

‘I just eat it like this?’

‘Yes, or on pizza or on toothpicks with pieces of cheese. When the stone’s been taken out.’

Cassie pops it into her mouth; surprised by the brassy bitterness, she scrunches up her nose, chews the olive flesh off the pit and spits it into her hand. ‘Will it grow if I toss the seed?’

‘I don’t know. How’s it taste?’

‘Different.’

‘Take the rest home. Try it with some cheese and crackers.’

‘Thanks, I have something too.’

‘Yummy, what is it this week?’

‘Me and Aunty Ida made butterfly cakes.’ Cassie retrieves the old cake tin from the bottom of her bag and hands it to Athena. ‘You can give the tin back next week. Or on Monday when you come down with the maths book.’

Athena sticks out her tongue and opens the lid. ‘Oh, I see you cut off the top of the patty cake, put in the cream and then put the top on so it looks like butterfly wings. Cute. It’s Ida and I, by the way.’

‘Ida and I,’ Cassie groans. ‘It’s just a butter cake recipe really.’

&

nbsp; ‘Yes, but it’s your Ida’s butter cake recipe. That woman is a genius.’

‘That’s why you should meet her. Hold on, two geniuses in one room, there might not be enough room for your head.’

Athena slaps Cassie’s shoulder. ‘Shut up, I’m not telling you anything anymore.’

‘Who else are you going to tell?’

‘True.’ Athena takes a cake from the tin and peels off the paper. She eats first one butterfly wing, then the other. Then she starts on the outside of the cake, methodically working into the middle.

‘Eat it already!’ Cassie complains.

‘I’m just savouring it.’

Cassie reaches into the tin. She peels off the patty cake paper and eats her cake in one mouthful. ‘That is how it is done,’ she says through the crumbs.

‘No wonder you have no friends.’

Cassie doesn’t answer.

Finishing her cake, Athena wipes her hands on her shorts and holds out her hand. ‘Can I look at your notebook now?’

‘There’s not much this week.’

‘Have you been preoccupied?’

‘Yes, with probability mathematics. Who cares what chance there is of getting a red marble.’

‘Gamblers?’ Athena takes the notebook from Cassie.

After much trial and error Athena developed a system. The notebook is divided into three main headings, Sleeping Dreams, Waking Dreams/Visions and Purposeful Telling, each with several subheadings, such as Vivid Dreams, Black and White Dreams, Sense of Foreboding, Trances, Tarot, Palm Reading. Each page is divided in two. When the ‘vision’ comes true, Cassie writes the details in the second column. Athena has veto if she thinks there is too vague a connection between the event and the vision. She rates each event out of five according to its relationship with the vision—five being clearly related. Athena admits it is somewhat subjective judgement, but the whole experiment, she says, is full of variables and difficulties and it at least puts some numerical value on the work.

There are many blank spaces in the right-hand columns. The mean score from Athena is two. It is not possible to calculate an average at this stage, she says. Maybe never. Mean is the best they could do for now.

The pepperina leaves are like delicate lace stitched with golden sunlight. Cassie takes another butterfly cake from the tin and peels the paper away. She takes a butterfly wing, scoops some cream onto it and tries to chew it slowly. In the distance, the roof of Athena’s house glints in the sunshine like a burning beacon.

‘What does this mean?’ Athena points to a dream from Monday. ‘“When the telescope moved, the whole world moved. Then I realised it was best not to look through it and the world stayed still.” The world? Can you be more specific?’

Cassie stares into the distance and searches for the dream memory. ‘It was like I was on a show ride. Like a Ferris wheel, but I wasn’t, I stayed in the same place and things shifted. As though the trees that were in the west moved a little to the south, and the floor beneath me slid, like an earthquake, but not shaking, just moving a bit to the right.’

Athena makes notes in the margin of the page. ‘You dream about telescopes a lot. And your brother. “And then Alex walked in” … that’s it? He didn’t do anything, say anything?’

‘He is just there, bugging me like always.’

Athena skims her finger down the page and turns to the section about Waking Dreams and Visions. Cassie wonders if she should have another of Athena’s cakes. She could eat an olive, but the idea doesn’t appeal to her.

‘What is this—“Mum and Dad go to the bank. The proof will be in the pudding”?’ You need to give me more detail. What happened that day?’

Paulo comes to mind and Cassie looks down at her feet. ‘I met Mum and Dad at the bank after school. I went and got a milkshake …’

‘Where?’

‘At Apollo’s’

‘Apollo’s is the name of the cafe!’

‘Yes, what’s wrong with that?’

‘Apollo was the god who cursed Cassandra—did I tell you that story? He taught her to read the future on the promise of a kiss but at the last minute she refused. So he cursed her. He said no one would ever believe her predictions.’

‘Well, nothing has changed then,’ Cassie replies.

‘What did they do at the bank? Apollo’s—really that is so … not like here.’ She waves around her at the general ruralness, the back waterness.

‘Yeah well, some wogs took it over and renamed it. It used to be Rosie’s. They had an appointment with the manager. For a loan to build another chook shed.’

‘More chooks!’

‘I know.’ Cassie laughs. ‘Like we don’t have enough. But I didn’t know about the loan or anything on the day. I only found out later when we got home and they talked about it to Poppy. It was Poppy’s idea, I think.’

‘So you met them at the bank, but you didn’t know why they were there?’

‘No, after the milkshake, I came back to the bank and they were coming down the stairs. Mum seemed worried but Dad was like all the world is his oyster. Mum said, the proof will be in the pudding, and I got that feeling, you know, like there is a tonne of bricks in my stomach and a pile of bricks on my chest and I couldn’t breathe. The one you said I should call a sense of foreboding.’

‘Maybe you were empathising with your mother’s worry?’

‘Empathising?’

‘Feeling what your mother felt.’

‘Oh.’ Cassie thinks for a while. ‘Except that my mother worries all the time. It’s like a hobby for her. If she sees me go outside without shoes she tells me I’ll stub my toe and get blood poisoning. I’ve seen her check Alex is still breathing in his sleep. He’s nine years old. What is he going to do, die of cot death in his single bed?’

‘Can you try and write as much detail as you can? It will make it easier in the long run.’

Cassie snatches the book from Athena.

‘Cassie?’

‘Yeah, yeah, more detail.’

‘Anything else you didn’t write down?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

Is Paulo branded on her forehead? Sometimes Athena seems like the mind reader.

‘I put everything in the notebook.’

‘You didn’t have any events to match up?’

‘No.’

‘That’s three weeks.’

‘I know. I’m going home.’ Cassie picks up the maths textbook.

‘Already? We haven’t done a Purposeful Telling.’

Cassie puts the book back on the ground and sighs. ‘I bought the tarot.’

‘I’d like to meet your mother,’ Athena says.

‘What? After all this it is my mother you want to meet?’

‘I know. It just came to me then. There’s something else I’ve been thinking about too.’

‘Yes?’ Cassie rips at the grass beside her, plucking the straggly strands from their bed of dirt.

‘We need a broader sample of Purposeful Telling. Can you do some at school?’

‘Maybe.’

‘Excellent. Where’s the cards then?’

Cassie reaches in her bag and draws out a bundle wrapped in a scarf, salmon pink, black and red. Cassie takes a breath and closes her eyes, holding the parcel aloft, the black fringe tickling her legs.

Athena sniffs. ‘That thing always makes me sneeze.’

Cassie opens her eyes, dumping her parcel on the ground. ‘It was Ida’s scarf. She gave it to me for dress-ups when I was little.’

‘It’s dusty.’ Athena rubs her eyes.

Cassie sighs, a deep exhalation. ‘I need to concentrate.’ She turns the scarf over and unties the knot and spreads the scarf like a table on the ground between them. She smooths it over the bumpy ground. From the centre

of the scarf she takes an incense stick and a box of matches. ‘For air,’ she mumbles, lighting the stick. Next she lights a candle in a small jar. ‘For fire.’ Between them she places a piece of volcanic rock and a seashell. ‘For earth and water.’

Last she picks up the box of tarot cards and cups them in her hands, breathes on them, and after turning them three times, clutches them as though only they exist. ‘Grant me sight,’ she whispers before opening the box and extracting the cards. ‘Do you have a question?’ she asks.

‘No, I don’t think so. Let’s just do an open one.’

Cassie concentrates on the pack of cards. A small shuffle seems appropriate. She shuffles and the cards stick together like best mates. Athena, Athena, Athena, she says over and over in her head. Ants crawl up her ankles, she swats at them. ‘Damn ants.’

She hands the pack to Athena who, without prompting, splits the deck in three. Cassie reunites the deck and, drawing cards from the top, working from the centre out, she deals the cards into a Celtic cross.

From the centre pile of three, she turns the bottom card.

‘The King of Swords.’ Cassie swipes more ants off her ankles and moves her legs from underneath her, hugging her knees. ‘What is important to this reading is your intellect. You are a person who is full of ideas.’

‘You need a tarot card to tell you that?’

Cassie ignores her and turns the next card. On it stands a young man, looking like a hobo, on the brink of stepping off a cliff. ‘The Fool,’ says Cassie.

‘No way!’

Cassie bites her lip and rocks forward onto the front of her feet. ‘Fools rush in,’ she mutters, and then a swath of clarity gleams across the card. ‘Oh! The fool’s bag, see?’ She points to the bag tied on a stick draped over the fool’s shoulder. ‘The bag holds the memories of your previous lives, the hills in the distance are new challenges. The Fool is always on a quest. This time I would say an intellectual quest.’

Athena huffs.

Next she turns the card closest to her feet. ‘For you, it is about telling people what you learn. I see you before a large group speaking. You must be careful of your sharp tongue, be careful you don’t boss too many people around. There is loss in this card too. A past loss. A grieving.’

Cassandra

Cassandra